At about 1:30 a.m. on February 14, 2005, forty-nine year old Betty Kennedy, an x-ray technician at Nelson’s Kootenay Lake Hospital, received a page to come in to the emergency department. Her boyfriend, Dan Popoff, offered to drive her but she told him she’d be fine and urged him to go back to sleep.

It was only a 15 or 20 minute drive to the hospital from her location in Blewett, and it was a cold but beautiful starry night. Dressed in a big London Fog coat and driving her new Honda CRV with heated seats, Betty was soon toasty warm and enjoying the drive. But less than ten minutes after leaving the house, rounding a tight corner onto a straight stretch, the vehicle fishtailed on black ice and flew off the road. Tumbling end over end down a boulder-strewn 30 foot bank, it punched through three inches of ice to land upside down in the Kootenay River in a small protected bay. Because of the isolated location and the time of day (1:40 in the morning), the accident went unnoticed by anyone.

While Betty hung upside down from her seatbelt, the vehicle rapidly began to fill with icy water pouring in through the broken hatchback window. In absolute blackness, she freed herself and wriggled up to the airspace above her to take a breath. With the top of her head pressed against the floor of the vehicle, the water came up to her chin. She had the presence of mind to try opening the doors, but they wouldn’t unlock. She tried to kick out the windows, but lacked the leverage or the strength to break them.

At that point Betty realized she was probably going to die. Trapped, she didn’t know how deep the water was or whether the vehicle was going to sink deeper. But then she found herself filled with resolve - her husband had died in a car accident two years earlier and she was not about to leave her four children without a parent. She found herself thanking God for all her blessings, for her wonderful friends and family, and for Dan. Ducking back under the terribly cold water, she searched by feel until she found the cell phone in her purse, but it had shorted out and was useless.

By 02:00, emergency room nurses Ruth Sutherland and Deb Pattyn began to get concerned when Betty hadn’t shown up in her usual timely manner. They paged her again, and tried calling her cell phone. There was no response.

Betty was desperately cold and was starting to lose control of her muscles, but she held on to the thought that the hospital would call Dan when she didn’t arrive, and he would come find her. She prepared herself to hang on for as long as it took.

By 02:15, Sutherland and Pattyn were worried enough to call Dan Popoff’s house. Unfortunately, having fallen asleep immediately after Betty left, Dan had lost track of how long she’d been gone, so he told them she'd only just left. But Betty had now been trapped in the freezing cold water for thirty-five minutes, and no one knew it.

In the pitch dark, Betty waited with chunks of ice floating around her neck, and something else bumped up against her face in the freezing darkness as well. For Valentine’s Day she had bought her children and Dan’s some little heart shaped plastic containers of Ferrero Rochet chocolates, and she found those containers miraculously floating in the car. Betty loved chocolate but had been denying herself in an effort to lose a little weight. She decided that if she was going to die, she might as well die with chocolate. Her fingers were too numb and frozen to open the containers, so she bit them open one at a time and ate as many as she could, although some fell into the water and were lost. She was very cold, and she kept praying for Dan to come and find her.

Dan was too worried to fall back asleep. At 02:30 he called the hospital emergency department to see if Betty was there yet, and when they said no he told them to call his cell if she turned up; he was going to go out looking for her.

He retraced Betty’s route slowly, looking for signs that she might have had an accident. An experienced hunter, he was attuned to looking for clues and tracks in the thin hard snow along the sides of the road. After rounding the corner onto the straight stretch before the highway, he had a distinct feeling that Betty might somehow have come to grief there. He went back and forth along that section of road several times but didn't see anything, and was about to head on down to the highway when he thought he saw faint marks on the pavement. He backed up to view that section of road again in his headlights, but could see nothing.

For a moment Dan was tempted to carry on, but he had a feeling of urgency that he couldn’t shake. He felt somehow guided. Climbing out of his car, he looked over the bank. The night was very dark but he thought he saw a faint gleam below, so he ran back for a flashlight. The beam of light revealed his worst fears - the undercarriage and wheels of Betty’s car were visible above the ice of the river.

Dan had lost his wife to cancer two years earlier and this was a nightmare he could scarcely bear. He cried out to Betty… and she answered him.

Betty had been enduring the freezing darkness for a little over an hour when she heard Dan’s voice shouting, “Betty, are you there?” Somehow, against all odds, he had found her! She screamed back, calling, “Dan, is it really you?” and he said, “Yes! Hang on, I’m getting help!”

At about 02:45, Ruth Sutherland called the Nelson ambulance station to see if there had been a car accident Betty might have been involved in. While Ruth was on the phone with the paramedics, Deb Pattyn answered the other line. It was Dan, saying he’d found Betty’s car in the river and he couldn’t get to her.

Dr. Trevor Janz was on duty in the emergency department that night. He heard the news with a horrible sinking feeling, knowing Betty’s chances for survival were not good. He looked at the nurses and said, “It’s over, she’s dead, she’s drowned.” They began preparations for a resuscitation effort for the cold water drowning of their friend, knowing that treatment for a hypothermia cardiac arrest would involve grueling hours of CPR while trying to warm the body and would most likely not be successful.

Back at the river's edge, although Dan’s instinct was to plunge in after Betty, he had been a volunteer firefighter with the Blewett Fire Department. He knew that aside from the fact that he wasn’t equipped for the conditions, if the car were precariously balanced any action on his part could cause it to slip into deeper water, with tragic consequences for the woman trapped inside. So he stood on the rocks of the shore, calling to Betty, telling her he loved her and encouraging her to hang on.

Nelson City Police Constable Paul Jacobsen was on duty at the police station that night. He received a 911 call from the hospital at about 02:45, but the location of the accident was outside his municipal jurisdiction. He passed the call off to BC Ambulance dispatch in Kamloops and RCMP dispatch in Kelowna.

BC Ambulance paramedics Deb Morris and Heidi Henke were dispatched to the accident scene at 02:48. Having already heard from the hospital, they were up and ready to go immediately.

Nelson Fire Rescue firefighter Bob Patton was on watch that night when a call came in at 02:50 from BC Ambulance dispatch with a report of a vehicle off the road and upside down in the river. Captain Bob Slade, the other member on duty, responded to the scene in Engine 2 at 02:55. While en route, Captain Slade was advised much to his surprise that the occupant was still alive and talking, so he told Patton to contact volunteer Fire Chief Al Craft of neighbouring Beasley Fire Rescue and have a couple of their swiftwater rescue personnel attend with their rescue boat.

RCMP Constable Steve Grouhel was also called at 02:50 with a report of a vehicle in the river, but he was a half hour away, even running code three with lights and sirens. Meanwhile, Nelson's Constable Jacobsen had been monitoring the developing situation. Aware that time was absolutely of the essence, he made the decision to leave his jurisdictional boundaries and respond directly to the scene of the accident.

Beasley Fire Chief Al Craft received a call from Bob Patton at 03:00, requesting a mutual aid response with Beasley’s rescue boat and cold water gear. Craft called his deputy chief, Fred Doerfler, telling him to suit up and meet him on scene, then went straight to the fire hall to get the boat and swiftwater rescue equipment.

Paramedics Deb Morris and Heidi Henke were the first emergency responders to reach the scene, at 03:01. Betty had now been in the water for 80 minutes. Despite a natural desire to jump in and get her out, they knew the situation was unsafe and that they needed more help. Accustomed to taking decisive action, they found the waiting very difficult. Morris called Nelson Fire Rescue to make sure Beasley's swiftwater rescue technicians had been requested. Then she called the hospital and told them Betty was still alive but that it would be awhile before they got her out. Henke concentrated on holding Betty’s attention, calling to her and keeping her talking.

Arriving on scene at 03:05, Captain Slade was amazed to find Betty still conscious. He radioed Firefighter Patton and told him to call someone in to cover him and to bring the ladder truck code three. He also called in Assistant Chief Simon Grypma, who lived nearby. Slade didn’t know how long Betty had been immersed, but it had been long enough that she wasn’t responding properly. He knew he was not equipped to enter the water, and he didn’t want to disturb the balance of the vehicle. With properly equipped rescue techs en route, he knew he had to stand by. He set up the lighting plant to provide some scene lighting.

Trapped in her upside-down car under the water, muscles absolutely rigid with cold, Betty was getting drowsy and felt herself slipping. But when she saw the light she knew she was going to be okay. She had been in the icy water for 90 minutes.

When Constable Jacobsen arrived at the scene, he was stunned by what he saw. It was a bitterly cold night, and the open water around the vehicle was refreezing. The situation felt absolutely hopeless. He wanted to drop his gunbelt and plunge in, but Betty was still conscious and talking and he knew he had to wait. He was aware that the icy water would suck the heat from him many times faster than the air, and that as soon as his muscles seized up he would be useless, resulting in one more patient and one less rescuer. He asked his dispatch to make sure the swiftwater techs were en route, and he called for a tow truck to help stabilize the vehicle.

Kevin Drake of Western Auto Wrecking lived nearby and was on scene with a tow truck within minutes. He backed his truck into position and pulled a cable down the bank.

Constable Grouhel arrived on scene at about 03:20. He could see Dan standing at the shoreline, yelling encouragement to Betty, but he couldn’t hear her replies over the noise of the generator. He too was immediately concerned about the stability of the vehicle, as it appeared that the only thing holding it above the water was the ice around it.

Nelson Fire Rescue Assistant Chief Simon Grypma arrived on scene shortly after Constable Grouhel, and after being briefed by Captain Slade he assumed command of the rescue operation. They discussed the possibility of going in after Betty but decided against it because of the risk to her as well as to the rescuers, deciding that the best course of action would be to wait another few minutes for the Beasley swiftwater rescue techs to arrive with the proper gear to enter the water safely. They realized that they had a very technical situation on their hands, especially in light of the fact that all the windows of the vehicle were under water, which meant that if they were to try to get Betty out in the position it was in, they would have to bring her underwater to get her out.

By this time, Betty was beginning to sound frantic and disoriented, and Dan was worried that she wouldn’t last much longer. Everyone knew they would have to work as a team, and work fast.

The paramedics had assessed Betty’s condition as best they could under the circumstances. They were only partially relieved when she told them she wasn’t injured, as she was literally freezing to death and was numb with cold. They knew she’d been wearing her seatbelt and had been able to move her arms and legs after the accident, which was good news. Because time was of the essence and access to the vehicle highly problematic, spinal injury concerns would have to take second place to speedy extrication.

Firefighter Bob Patton arrived with the ladder truck at 03:23, and Grypma staged him to set the ladder up. They considered running a rope from the ladder to stabilize the vehicle, but it wouldn’t drop low enough for that. It did, however, make a fantastic platform for overhead scene lighting.

Beasley Fire swiftwater rescue techs Craft and Doerfler arrived moments after the ladder truck, and Grypma and Slade briefed them while helping them don their gloves and PFDs. Grypma felt that Betty had maybe eight inches of airspace and seemed to be fading, so they had to be prepared for the worst case scenario. He wanted them to see if the rear hatch would open, as the vehicle was a little higher in the water at that end.

Patton handed them a window punch, and they descended the bank with the help of a rope tied off to the aerial truck. They had to break through the ice to get to the vehicle, but fortunately the river bottom was flat in that spot and the water was only about four feet deep. They called out to Betty to tell her they were coming, and she answered. Once they got to the vehicle, they tried to open the rear hatch, but without success. They were unable to access her through the rear window due to obstructions such as debris and high headrests. They popped a couple of the side windows underwater but they couldn’t reach her, and they were unable to open the doors of the damaged vehicle. As they worked, Craft and Doerfler continued to talk to Betty. Sometimes she answered them, but sometimes she didn’t. It renewed the rescuers’ sense of urgency. They knew time was running out.

Craft felt they could use the wrecker to roll the vehicle to one side in order to expose a window to gain access, so they hooked the tow cable onto the far end of it. Drake started pulling the car toward shore and rotating it to one side while Grypma oversaw the careful orchestration between the crew in the water, the crew on the shore, and the tow truck operator.

Constable Grouhel held his breath, hoping that the car wouldn’t dislodge and slip into deeper water. Drake continued to pull cautiously, rolling the vehicle up and onto its side until the rear driver’s side window cleared the water (see photo above). Doerfler shone his flashlight in, and there was Betty lying with her legs between the front bucket seats and her head in the foot well of the back seat.

Craft reached in through the window and grabbed Betty under her arms. Doerfler managed to grasp her belt, and together they carefully floated her on her back out the window and over to the shoreline where Grypma and Slade had put Nelson Fire’s basket stretcher into the water. They were able to float her (along with a lot of broken ice) right onto the stretcher, and the assembled crew lost no time bringing Betty up the bank to the waiting ambulance, with Jacobsen, Grouhel, Patton and Drake helping with a relay pull on the rope from above.

Betty’s eyes were as big as saucers. “Is this really happening?” she asked. “Is this really real?” She was shivering uncontrollably, still clutching the lid of a Ferrero Rochet chocolate container to her chest. She had been trapped in the freezing water for two hours.

The paramedics immediately went to work, cutting off Betty’s wet clothes and wrapping her in blankets. Betty’s skin was so icy cold that when Henke touched it she halfway expected to stick to her, like frost.

As the ambulance pulled away, there was a lot of high-fiving and hugging among the rescuers on scene, but their jubilation was tempered by the knowledge that Betty was not yet out of the woods.

An adult’s normal core temperature is 37 ºC, and hypothermia begins at about 35 ºC. Most people lose consciousness somewhere between 32 and 30 ºC, cardiac arrhythmias tend to occur at 28 ºC, and temperatures lower than 27 ºC are almost always fatal. Severely hypothermic patients are fragile and often die after being rescued, because after removal from the water the cold blood in the extremities can begin to circulate back to the core and cause a further drop in body temperature. Betty had been safely rescued from the icy water, but there was more work to be done to save her life, and it was now in the hands of the medical professionals.

Arriving at the hospital at 04:03, Betty was taken straight to the trauma room for treatment. She was profoundly cold; in fact she was now too cold to shiver. She was confused and barely able to respond, and her core temperature was initially measured at just 27 ºC. The ER team started her on warm IV fluids and used a warming blanket called a Behr Hugger to blow warm air around her. They carefully warmed up bags of saline in the microwave to use as hot packs because anything too warm would burn her extremely cold skin. Dan stayed at Betty’s side, beside himself with worry.

As she grew warmer, Betty began to shiver violently and to apologize for all the trouble, saying, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry.” Overcome with emotion, Dr. Janz and fellow x-ray tech Marg Dietrich bent down to hug her. Janz put his face against her cheek and said, “Oh, Betty, we’re so happy you’re still alive!” Eventually she drifted off to sleep.

Betty’s extraordinary survival is due to a number of factors, not the least of which was her refusal to give up. Fortunately, she was very warm when she hit the water, and she was wearing a big coat that helped to conserve some body heat. She was not in moving water, and she remained relatively motionless (attempting to swim in near-freezing water causes a greatly accelerated rate of heat loss). And the chocolate, with its sugar, caffeine and calories, gave her some extra energy.

“There’s no way I could have withstood what she went through,” says Constable Jacobsen. “She had a will like nobody I’ve ever seen, that’s for sure.”

Captain Slade is similarly impressed with Betty’s survival. “After all the unpleasant things we see, it’s really wonderful to have an outcome like this, to have someone survive who would otherwise have died.” But he is quick to give credit where credit is due: “She survived as long as she did,” he says, “because she had fortitude.”

Beasley Fire Chief Al Craft agrees. “We attend so many horrific scenes, and see so many fatalities. Over the years we’ve pulled a lot of bodies out of vehicles and rivers, and to have one end so well has been indescribable.”

Nelson's Assistant Chief Simon Grypma is very pleased with the overall effort: “Often during emergency response operations, decisions are made without recognizing that for every action there is an opposite and sometimes deadly reaction. In this case each responding agency identified the potential danger to the victim and saw that a premature rescue attempt could have resulted in the loss of the life-saving pocket of air in the vehicle. Everyone recognized the need for a joint rescue operation combining the different resources provided by multiple agencies, and the success of the operation is a reflection of individual training, knowledge, and willingness to work together as a rescue team.”

Betty Kennedy and Dan Popoff have since gotten engaged. They plan to get married next year, some place warm … on Valentine’s Day.

- Monica Spencer

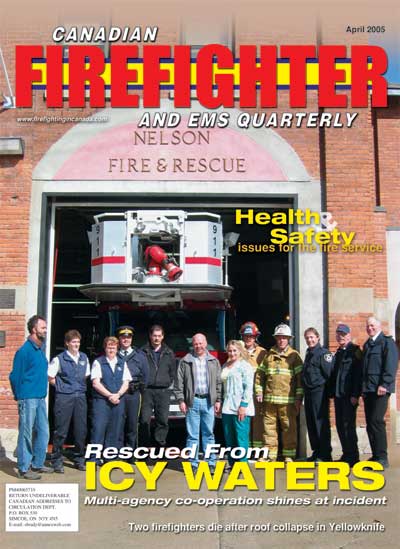

Above, left to right: Dr. Trevor Janz, paramedics Deb Miller and Heidi Henke, RCMP Constable Steve Grouhel, tow truck operator Kevin Drake, Dan Popoff, Betty Kennedy, Captain Bob Slade, Assistant Chief Simon Grypma, firefighter Bob Patton, Fire Chief Al Craft, Deputy Chief Fred Doerfler.

Above: Beasley Fire Chief Al Craft surveys the location the next day.